Kahlil Gibran, one of the great artists of the twentieth century, was born on this day, 6th January, the day of Epiphany, in 1883, in the village of Bisharri, Lebanon. It was an age when the unknown and mysterious ways of the East were opening up to the adventurous West, through what was not necessarily a welcome quest, colonialism, much of it by the British and the French. But it was also a time when a new consciousness was being born, as many Western writers and thinkers became inspired, not only by the new translations of some of the East’s great spititual texts, such as the translation of the Upanishads by the Irish poet, Yeats, but, also, by their arts and traditions.

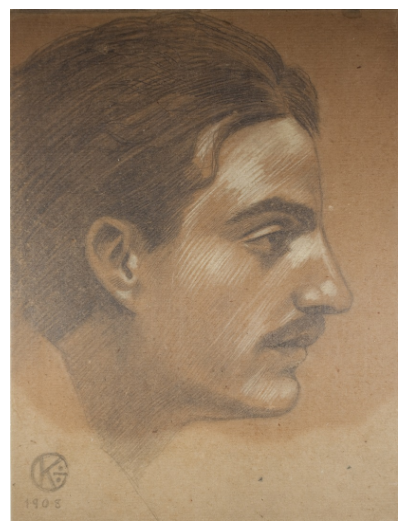

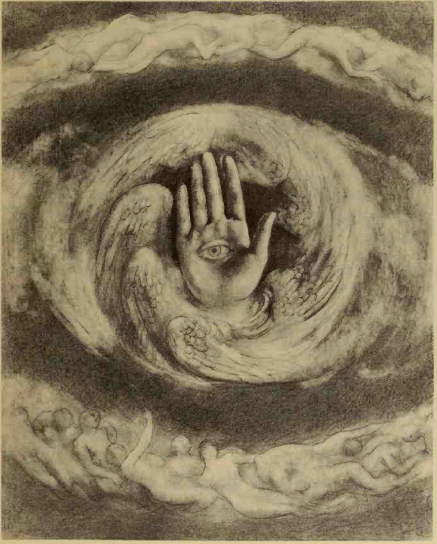

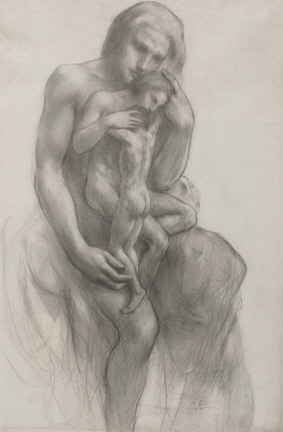

Like Rabindranath Tagore, Gibran, in his spiritual and political writings in both Arabic and English, became a creative force to help bring the traditions and culture of East and West together, a kind of marriage of opposites. His stories, parables, essays and poems were infused with an ancient yet timeless wisdom that spoke of life and death, love, friendship, beauty, sorrow and joy, and dreams. His moving paintings and drawings show the influence of Rodin and William Blake, whose work was introduced to Gibran by Rodin.

He was brought up a Maronite Christian, but he believed in the unity of religions, and sought to reconcile Islam with Christianity. He sought, also, to reconcile the sacred with the profane, that which was spiritual with that of the material, and the nature of our inner life with that of our outer, in a search for harmony. He did not believe that politics were a solution to conflict and strife and abhorred violence, but had faith, more, in the living spirit of humanity as healer. He said, “To be closer to God, be closer to people.”

His beautiful book, The Prophet, was one of the most influential books of that age and is still read today. His words and images had various moods, a music gentle as a breeze caressing the leaves of a tree or bubbling like a soothing stream. Yet his work was not without anger and despair at the ruthless ways of the world and, at times, with great intensity, could be a violent storm and sweep up our emotions in its great wind and throw us to the ground, or burn us with the passion of a raging fire. He gifted us with pearls of wisdom, as in the parable, “The Pearl,” the entirety of which I shall quote here and from which those of us in pain can take heart at its message.

“Said one oyster to a neighbouring oyster,”I have a very great pain within me. It is heavy and round and I am in distress.” And the other oyster replied with haughty complacence, “Praise be to the heavens and to the sea, I have no pain within me. I am well and whole both within and without.” At that moment a crab was passing by and heard the two oysters, and he said to the one who was well and whole both within and without, “Yes, you are well and whole; but the pain that your neighbour bears is a pearl of exceeding beauty.”

His work was sourced from mystery and wonder, from love and a yearning heart, as well as a knowing humility, for as Poet, Aritist and Mystic, he saw with the inner eye and heard with the inner ear and said, “There is a space between man’s imagination and man’s attainment that may only be traversed by his longing.” It is interesting to note that Rodin recognised this senstivity and depth in his work and preferred his portrait to be painted by Gibran than by any other artist.

When he was twelve years old he emigrated to America with his family and settled in the Boston ghettoes, later living in New York City, where they lived a difficult life, fraught with poverty and illness. But the American people and culture, nevertheless touched him deeply and he developed a burning desire to create. “I came to this world to write my name upon the face of life with big letters,” this statement, itself, an epiphanic prophesy.

The fracture that was his separation from his beloved Lebanon, left him with much pain and a tragic sense of life, for he missed it terribly and worried about the conflicts that were ravaging his country and the Arab world. This longing for his homeland created a deep struggle within him, and he felt himself to be a wandering spirit. Still, there was joy, too, in the beauty of life, and he saw in all things a spiritual trancendence. “I would not exchange the sorrows of my heart for the joys of the multitude. And I would not have the tears that sadness makes to flow from my every part turn into laughter. I would that my life remain a tear and a smile.” This from “A Tear and a Smile,” a series of tales and prose poems.

Nature was his mother, and as a somewhat wild child, he would run outside on stormy days into the lightning, charged by the turbulent light that broke the sky, and would experience the whirling wind as the furling and unfurling of wings, the energy and creative urge of nature and the universe, fostering in him a kind of “madness,” as he called it, and from which stemmed much of his creative genius, but which, sadly, also, took a toll on his health. But there lived in him, too, the hermit, who longed for solitude.

He had an affinity with trees, and as an adult the memories of the peaceful village of his birth with its beautiful countryside, of which he particularly revered the majestic and Holy Cedars, would give him spiritual sustenance, and searched for places of nature to find sanctuary away from the hectic life of the city. He could see that with sorrow would come the joy of life’s sweet song for as he says in The Prophet, “And is not the lute that soothes your spirit, the very wood that was hollowed with knives?” Gibran, himself, was a many-stringed being tuned to the song of heaven and earth, and I have been much inspired and moved by the beauty, power and wisdom of his work. To me, he is still a prophetic voice for our time. Kahlil Gibran died in 1931 in New York City, when he was only forty-eight years old. He was buried in the land of his birth, in the small village of Bisharri, Lebanon.